Yesterday When I Was Young

Someone said that if Leonardo da Vinci had to tweet five times a day, people would still be riding bicycles. But modern living with all the technology has made us empty. We are mostly half-present with the other foot in the digital world somewhere. Modern life has created an urban dweller who is more isolated in the big city than his ancestors were in the kampong. Today, modern living fail me. My astro television subscription got cut off, my attempt at online payment failed, my mobile phone had a flat battery, and my laptop went missing. There was no television to watch my favourite Fox movies, no mobile phone to chat on, and no internet to browse or “google” (it seemed “google” is now accepted as a verb in modern English).

About figure – Suspended umbrellas on Jonker Street, Chinese New year, Malacca town

Suddenly I had plenty of time on my hands. My mind began to wander back to the 1960s. Just how did yesterday’s 9 year olds lived in the 1960s and 1970s, back in the then little town of Alor Setar, with almost no technology? We watched black & white television, and listened to only one radio channel. People took time to communicate with each other by having real conversations and not through whatsapp. Young people back then took time to read print books because print media was the only way they could get any information and bask in their imagination. I used to read a lot of books, the Enid Blyton Famous Five series and as I grew older, spy thrillers, such as “The Day of the Jackal” by Frederick Forsyth, first published in 1967. I doubt any of my children ever heard of the book.

In the evening I would cycle outside on the dusty laterite road on my father’s bicycle twice my height. Riding an over-sized man’s bicycle was tricky. It required children to contort and wrap their bodies underneath the horizontal crossbar in such a way that their legs could reach both pedals, their hands could steer the handle bar while safely remaining in almost perpetual motion. If only a machine of perpetual motion is possible. Regardless, I landed headlong, together with my over-sized bicycle, into the green slimy ditch when the bicycle veered to the side and the brakes failed me.

But nothing beat the experience of catching fighting fish in the dark murky swamps behind my kampong house. It never occurred to me then that there could be a python or water snake slithering in the dark mangroves. Now I would squirm at the sight of a rattlesnake on National Geography television. We would be so engrossed with catching the fighting fish that we almost always hardly noticed the setting sun. On weekends, we would go out to play with the morning sun and head home with the setting sun. On one occasion, I remember a second cousin being chased around the kampong by his 80 year-old grandmother because he came home late. He was hoping to outrun her as the chase would probably tire her out. But with a stick waving in the air just inches above his head, he was not about to take any chances.

Back then a household would have one bread winner present to take care of the home. Parents of that period practically allowed us children to be doing our own thing. I would like to think I was much happier than children of nowadays living in a big city like Kuala Lumpur. Modern mothers, hovering over their children about homework, or in anticipation of some danger lurking round the corner and fathers who never were quite home is the norm nowadays.

But my father was always home at magrib. I recall my father was a man of few words and deeply, deeply religious. He was a chief clerk in the land office in Alor Setar, and he cycled to office everyday. I remember I was 5 or 6 years old running around in my skirts when I joined my father for magrib prayer. He never uttered a word as he turned around to check the saf. His gentleness and patience encouraged us all towards prayers. He hardly laid a hand on us or caned us as far as I could remember except for that one time. Perhaps it was to teach us some much needed discipline. My mother on the other hand, was illiterate and not able to read except for some jawi with a little rumi. She loved to socialize, visiting friends for long hours.

Don’t get me wrong, we children of the 1960s had our fair share of responsibilities. We washed, starched and ironed our own school uniforms especially during secondary school days. During those days the girls uniforms had box pleats and ironing starched box pleats was no mean feat especially if you had only coal-fired metal irons to press clothes. Coal-fired metal irons were heavy and impossible for a child to handle. But washing school shoes on weekends was a breeze. We helped our mothers sweep the floor or buy groceries from the nearby shop run by a Chinese family.

I walked to school when I was seven years old. When it rained heavily, the river would swell, the fragile wooden bridge would be swept away by the strong currents and we had to skip school that day because there was no way of crossing the river to the other side. Sometimes I would take off my school shoes if it rained, at the risk of my feet getting cut by broken glass buried in the mud, only so that my shoes would remain sparkling white when I finally get to school that morning.

School of yesterday was not as burdensome as school of nowadays. There was no tuition classes when we were 10 years old. But punishment was considered necessary. Wrong answers in class would mean a painful crack on the knuckles with the corner of a blackboard duster by the teacher. Knuckles would get swollen but we never felt the need to report back to our parents as we took punishment as part of learning. Perhaps we were tough kids back then.

I would like to believe that the punishment paid off, turning many of us into upstanding citizens. We became decorated naval admiral, school teachers, scientists, chemical engineers, mechanical engineers. If there was anything to be proud of, two prime ministers of Malaysia called Alor Setar home, one even returning to serve for the second time at 93 years of age. Alor Setar was also home to the first woman deputy prime minister of Malaysia, an achievement for kampong boys and girls like us, many with parents who were unschooled and illiterate.

“Yesterday when I was young

The taste of life was sweet as rain upon my tongue

I teased at life as if it were a foolish game

The way the evening breeze may tease a candle flame

The thousand dreams I dreamed, the splendid things I planned

I always built, alas, on weak and shifting sand………………………”

Charles Asnavour

Rumi, the Sufi Saint in Konya

Among the Middle Eastern countries, Turkey is second only to Israel in terms of having the most number of biblical sites. According to Temizel & Attar “Faith Tourism Potential of Konya in Terms of Christian Sacred Sites” (European Scientific Journal, July 2015), Konya has biblical significance for the Christian world. It was mentioned in the New Testament that Konya was one of the cities visited by Apostle Paul.

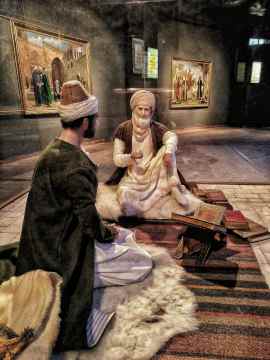

About figure – The Konya Culture Centre contained exhibits of Rumi and all related events during his lifetime of Sufi work.

Today, however, Konya is famous for something else. It is famous for its mosques, its theological schools and its connection with the great Sufi saint Jalaleddin Rumi (better known as Mevlana), the founder of Mehlevi order of whirling dervishes. Rumi was a 13th century Sunni Muslim poet, jurist, Islamic scholar, Sufi mystic. Rumi’s influence transcends national borders and ethnic divisions: Iranian, Tajiks, Turks, Greeks, Pashtuns and other Muslims. Today three countries claim Rumi as their poet: Iran, Afghanistan and Turkey.

About figure – This particular exhibit showed Rumi discussing with his spiritual instructor, Shams of Tabriz, who changed his life forever & his manner of thinking.

Konya is about 225 km from Goreme by road. It used to be a one-street town in 1972. After 45 years, it transformed into a big bustling city, modern and vibrant. We took a bus to Konya for one reason only…….to visit Mevlana Museum. Unfortunately, the culture centre was closed by the time we got there. A notice at the reception hall announced that a sema was supposed to be held on 17th December, the anniversary of Rumi’s birthday.

A sema (according to https://turkeytravelplanner.com) is a mystic religious rite. It is an elaboration of the whirling Rumi did while lost in ecstasy on the streets of Konya in the 13th century. A sema ceremony has seven parts symbolizing the dervishes love for God, humankind and all creation. The seven parts are: 1) praise for God, Muhammad and all prophets before him; 2) beating of kettle drum symbolizing God’s command “Be”; 3) Soulful music of the Ney symbolizing breathing of life into all creatures; 4) greeting symbol of the soul being greeted as the secret soul; 5) whirling and dropping of their black cloaks to reveal white costumes, symbolizing the casting off falsehood and the revelation of truth, with each dervish placing their arms on the chest to symbolize belief in Oneness of God “the One”; 6) Prayer involving recitations from the Quran and 7) Recitation of the Al-Fatiha, first surah of the Quran. Often Non-Muslims mistake Sufism as a sect of Islam. Sufism is not a sect of Islam. Sufism is more accurately described as an aspect or a dimension of Islam. Sufi orders or Tariqas can be found in Sunni, Shia etc groups.

Fortunately for us on that day, the young caretaker, Ibraheem, who saw us fiddling with door knobs trying to get the doors to open, was kind enough to open the exhibit hall just so we could have a quick visit, since we came from very far. We went down the staircase into a hall of the Konya Culture Centre with a number of interesting exhibits on display .

It seemed Rumi used to be a religious teacher until he met Shams of Tabriz. Shams of Tabriz completely transformed Rumi from a learned religious teacher into the world’s greatest poet of mystical love. Shams once told Rumi:

“Your preoccupation should be to know ‘Who am I, what is my essence? And to what end have I come here and where am I headed and what are my roots and what am I doing this very hour and what is my focus?”

(From Shems Friedlander of “Forgotten Messages”).

Its only knowing where we come from, can we appreciate where we are going. Life is not something that just happens. We are created for a reason. According to Ata’Illah

“The purpose of the rain cloud is not to give rain; its purpose is only to bring forth fruit”.