Kyoto is synonymous with incredible temples, cherry blossoms, parks, markets, serene gardens, tea ceremonies, traditional ryokan and craftsmanship. It was once the imperial capital of Japan with the finest gardens developed over centuries by many levels of society namely the aristocrats and the monks. Kyoto was voted by travelers as the world’s best city, twice. Seoul, SK is another thrilling city to visit

Sacred Spaces in the Garde

Figure 1: Another view of the Golden Pavilion, the beautiful Kinkakuji temple

It’s common knowledge that Japanese regard religious practices of Japan as part of the nation’s culture rather than a matter of individual belief or faith. As such many Japanese observe many rites: rites of the native Shinto religion, and those of Buddhism and even some of Christianity. It is therefore not surprising for a Japanese to celebrate a local festival at a Shinto shrine, hold a wedding at a Christian church and conduct a funeral at a Buddhist temple.

But when it comes to gardens, Buddhism shapes the way Japanese gardens are designed. The style of a Japanese garden both depicts the core of Buddhism as well as the anxiety of civil wars that raged throughout the country in the second half of the Heian Period (8th century to 12th century). The wars made people recognize the precariousness of life. The incessantly altering state of the garden echoes the Buddhist teaching about impermanence of our being and the never-ending cycle of death and rebirth. People find reasons to be more sensitive to the momentary beauty of nature and the changing of the seasons – plants budding, flowering, changing of the leaf colors and magnificent blooms dropping off with the approach of autumn, and colourful foliage that fade in the bitterness of the winter.

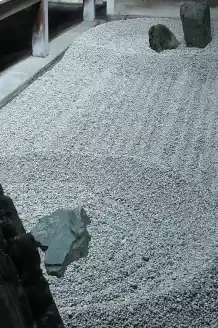

While the Heian gardens mirror the unpredictability of life, the Muromachi rock gardens completely rejected transitory facades of the material world. Garden makers in this period stripped nature bare. Zen gardens were created mainly out of rocks and sand in order to reveal the true substance of life and nature. During this Muromachi period, the growing influence of Zen Buddhism and its emphasis on contemplation led to a change in garden design. The purpose of the zen gardens were to provide the monks with a “place to walk and contemplate Buddha’s teachings.” The design of the garden was supposed to promote a feeling of peace and harmony in a space. By the 13th century, Zen gardens were heavily integrated into Japanese life and culture.

Figure 2:The aesthetic kyoko-chi pond for contemplation at the Golden Pavilion, Kinkakuji.

The garden in one of the most famous temple in Japan, the Kinkakuji, is an extraordinary example of a Japanese strolling garden of the Muromachi period. A path leads around the kyoko-chi pond (Fig 2) offering great viewing access for beautiful shots of the temple. The richly-decorated golden temple seemed to float over the pond.

The Ninna-ji temple represented a balance between aristocratic elegance and Buddhism simplicity (https//jal.japantravel.com). The temple was established in 888, during the Heian period, and is situated in north west Kyoto, a short distance from the Ryoan-ji temple. The gardens of Ninna-ji temple became the model for many Japanese gardens. The white sands were raked to perfection (Fig 3) to reflect waves. Figure 4 shows the pond in the North garden.

Figure 3: Neatly-raked sand at Ninna-ji temple to reflect waves.

When it comes to garden fencing, famous temples like the Ginkaku-ji and the Kinkaku-ji have their own styles. Traditionally materials like bamboo and wood or brushwork are used for fencing. Bamboo is is one of the most versatile, fast-growing and sustainable material. It is an integral part of daily life in Japan and provide material for many Japanese traditional crafts. Bamboo ages gracefully over the years – the fresh green fades to a honey colored gold and ages with time to a silvery grey. Moss has also been a central element of the Japanese garden for centuries. There are over 120 types of moss used in the Zen gardens. Figure 5 shows moss growing around a tree near the entrance to the Ginkaku-ji temple garden. Moss can keep water up to 20-30 times its own weight.

Figure 4: The Ninna-ji north garden pond with rocks, arranged together with the trees. The 5-story Pagoda formed a balance in the background.

A well-constructed Zen garden draws the visitor / viewer into a state of contemplation. The garden, usually relatively small, is meant to be seen while seated from a single view point outside the garden, such as the porch of the hojo , the residence of the chief monk of the temple or monastery.

Reduced colors and little vegetation let the eye rest and calm the mind, giving the garden a peaceful atmosphere. This is where a subtle, yet intriguing design feature of Japanese gardens comes into play – The carefully raked gravel patterns of rock and sand gardens. When the low morning or evening sun casts long shadows in the garden, the texture of rocks and gravel take center stage.

Figure 5: Beautiful moss growing around a tree in Ginkaku-ji zen garden, temple of the Silver Pavilion.

Zen stones are placed in Zen gardens to represent various elements of life (Fig 6). Stones are natural and reflect the balance between man-made structures and nature. Zen stones represent what is not actually featured in a Zen garden, such as islands and water. Each rock shape and formation has a different name and is represented by one of the five elements- kikyaku (earth), shigyo (fire), shintai (water), taido (forest) and reisho (metal).

Reclining rocks that are placed in a Zen garden to represent the earth are called Kikyaku. This stone is often known as a root stone and is placed in the foreground to bring harmony to the garden. Shigyo represents the fire element. When placed in a Zen garden, Shigyo stones are called branching and peeing stones. Shigyo stones arch and branch out, the way a fire looks. They are placed next to other shapes in a Zen garden. Stones which are horizontal and flat represent water in a Zen garden, and also the mind and the body. These stones called Shintai, harmonize rock groupings (Fig 7). Stones which are vertical and tall act as high trees in the garden and are also known as body stones. Taido stones are put into the back of other rock groupings, much like a forest is the background to other scenery. Reisho stones (also known as soul stones) represent metal. These stones are vertical and low to the ground. When placed in a Zen garden, Reisho stones are often put with tall, vertical stones such as Taido (www.sciencing.com).

Figure 6: 15-rock Zen garden in Ryoan-ji temple, the famous rock garden was created by a highly respected Zen monk, Tokuho Zenketsu. Only fifteen rocks and white gravel are used in the garden. Fifteen (15) in Buddhist world denotes completeness.

Figure 7: Totekiko garden in the east of the Ryogen-in temple is the smallest stone garden in Japan where the small traces of wave pattern remind visitors of the far-reaching ocean.

For curious tourists, who may not be a follower of any particular faith, participating in a meditation session in Ninna-ji or any other temples under the guidance of a monk (Fig 8) should be an interesting eye-opening experience. However, one Tripadvisor member warned to not walk into the meditation room during a session, because the monk might just give you a very unholy reprimand.

One thing that I took away from the temple garden visits in Kyoto, was one profound saying. The saying I found in Ryoan-ji temple was as follows: “When I change, everything else changes”. Someone used this saying during a management course I attended a very long time ago, a Zen philosophy we could all use in our daily lives.

Figure 8: Student monks I met at the front gate of Ninna-ji entrance. These student monks were trained on various areas such as tea-ceremony, meditation, etc.